途识马老 (‘An old horse knows the way’)

The Chinese veneration of their elders has endured throughout the centuries. Age brings wisdom and honour. Importantly, death is not thought of as a disconnect with that person – in fact, the spirit of the deceased can bring health, long life and prosperity to the family. However, the spirit of the dead will only bestow those accolades if he/she was properly honoured and valued in life.

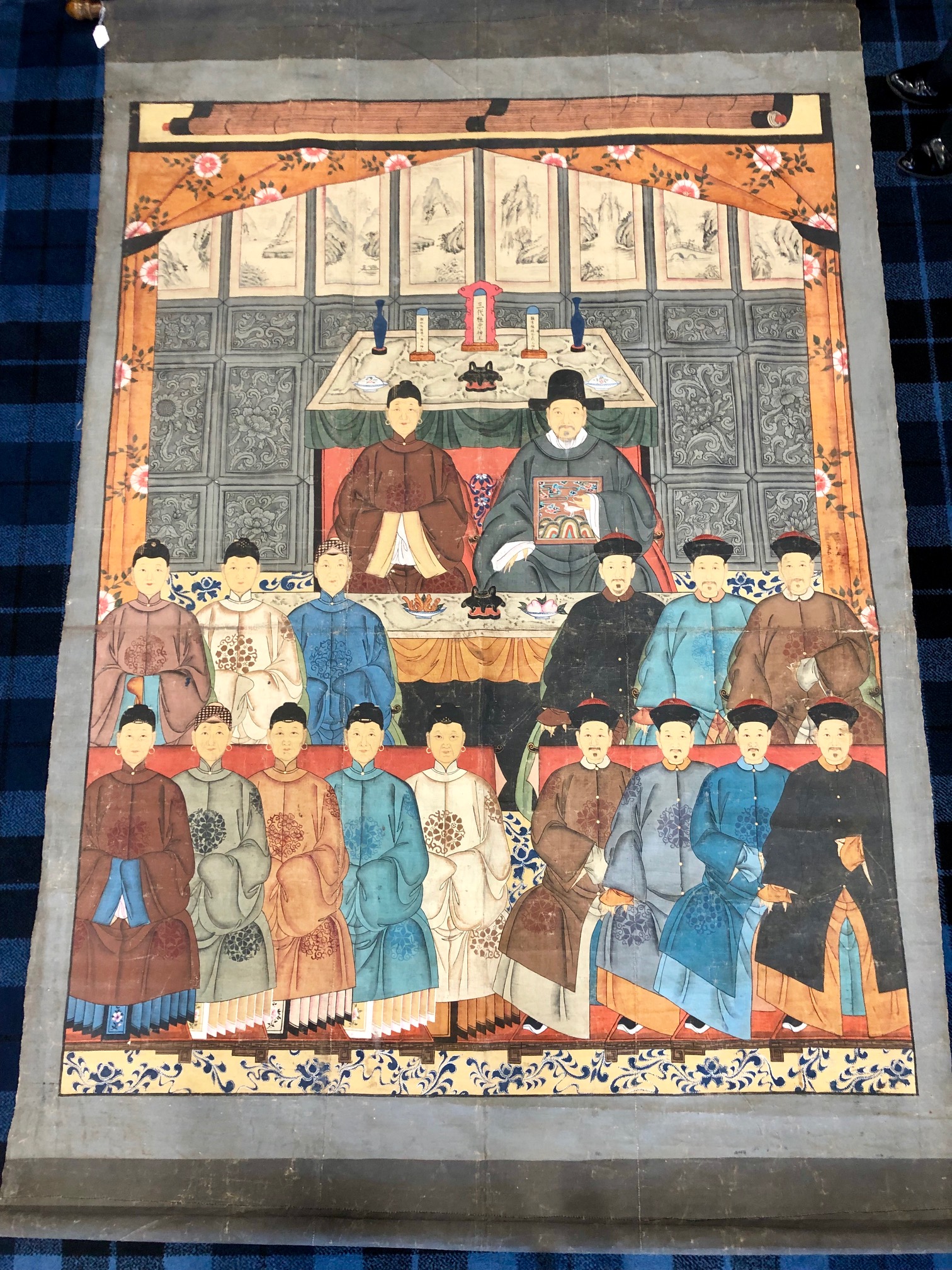

So one can understand the Chinese tradition of venerating their elders. Deceased ancestors were treated as well as the living elders. Food offerings were made to the ancestors, placed in front of scroll paintings. ‘Ancestor paintings’ – portraits commemorating the dead – were painted specifically for the purpose of veneration. Most of the ancestor portraits that have survived depict members of the Qing imperial families and military and civil elite who ruled China from 1644 until the revolution of 1911.

Usually life sized depictions of figures, the paintings portray the family member or members dressed in elegant robes and often seated in an elaborately carved chair. The ancestors generally wore semiformal winter gowns or fur-trimmed robes with elaborate insignia that proclaimed their rank. The only differences are gender-related: the women’s feet, considered the most erotic part of her body, were always hidden; most women’s hands were also hidden as well. Both men and women are often shown wearing long jade bead necklaces and elaborate headdresses with gold and pearl ornaments.

Imperial China was all about rank. Ancestor paintings reveal much about one’s rank in society – from the clothes one was allowed to wear, even the colours of the clothing, the jewellery, rank badges and hair styles. Important to the family commissioning the ancestor painting was the capturing of a good likeness. However, as the sitter or sitters were generally painted posthumously, this could prove tricky. A living relative was used, or a book of facial feature types (like templates), and a resemblance was considered very important.

When photography came into the picture, ancestor painting started to die out. Everyone who was anyone was now photographed, rather than painted.

In the Western art tradition, portraiture has been long established as a recognised art form, collected the world over, bought and sold by individuals and institutions. Chinese ancestor painting, however, has only relatively recently been considered works of art, and museums and galleries are seeing an increase in their trade and popularity. In the traditional Chinese family of the ancestor painting period, the painting itself was not for general consumption. It was for the family to view and venerate; private and personal. As such, a family would not have considered selling on the painting or buying another family’s painting. This position has changed and is still changing in China. Collectors are investing in ancestor painting as works of art of social and historical importance. The paintings tell us much about Chinese traditions and culture, dress and social structure. One must not judge them from a Western aesthetic – don’t look for photorealistic representations and emotive renditions. Instead, appreciate the other worldly quality, an expression somewhat detached from this world, and elevating the status of the person from the realm of the living to that of an icon for veneration.

The Asian Works of Art Auction, 18 July, features a stunning Chinese ancestor painting (lot 1017). Of impressive proportions and detail, this painting depicts a family of great standing. Take the chance to own this exciting work of art and study the many faces at your leisure – it holds many treasures to be discovered.

Magda Ketterer

The next Asian Works of Art Auction takes place on 11 October; entries are invited for this international auction. For a complimentary valuation please contact specialist Magda Ketterer on 0141 810 2880 or magda@mctears.co.uk.

What's it worth?

Find out what your items are worth by completing our short valuation form - it's free!